Kornberg Lab

For many animals, rapid divisions during the first stages of embryogenesis generate a population of undetermined cells that acquire developmental distinctiveness only as they prepare for gastrulation. These first stages have been thought to contribute little or no spatial information, and in animals such as amphibians, fish and insects, to rely entirely on maternal stores. In Drosophila, for example, the early divisions proceed with a cycle time of 9.6 min, and reportedly without gene expression. We discovered a small cohort of genes that is expressed at the early, pre-blastoderm stages. We found that one of these genes, engrailed, is expressed in embryos that have only two nuclei, and that engrailed mutant embryos develop abnormally at these stages (Ali-Murthy et al, 2013). These findings reveal that the zygotic genome is expressed and is essential in the very early stage embryo, thereby putting to rest the idea of a quiescent zygotic genome and opening the earliest stages of embryonic development to genetic and molecular analysis.

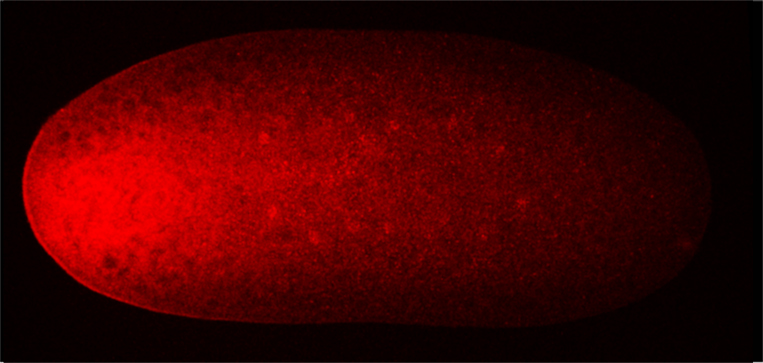

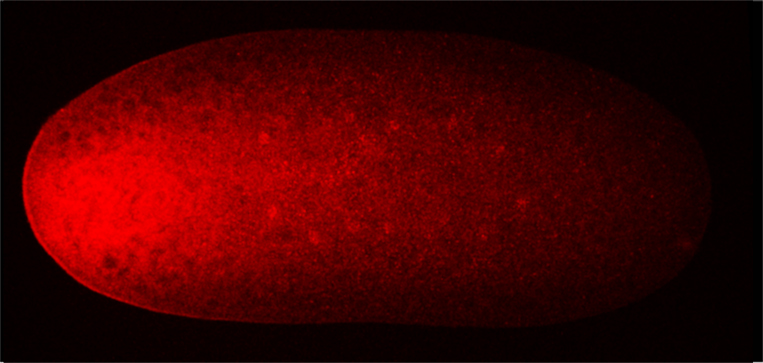

In addition to these studies of gene expression in the early embryo, we investigate how the early embryo is patterned. Thirty years ago, the first concentration gradient of a morphogen signaling protein was discovered - the Bicoid (Bcd) gradient in the Drosophila embryo. Genetic histological experiments showed that the Bcd concentration gradient organizes the embryo’s anteroposterior axis by regulating the expression of target genes, and showed that the gradient forms from bcd mRNA that had been sequestered in an inactive state at the anterior end of the unfertilized egg. It was proposed that the Bcd protein gradient forms after egg activation from newly translated protein that passively diffuses from its site of synthesis at the anterior end, and this model has been in our textbooks for several decades.

This model is predicated on several assumptions that had been unquestioned until now. One pertains to the idea that the egg lacks Bcd protein, an idea that was based on the observation that immature oocytes have bcd RNA and no Bcd protein. However, because no methods were known that could be used to examine mature oocytes, it was assumed that the mature unfertilized egg also lacks Bcd protein. The second pertains to the identity of the Bcd gradient itself. All studies of the Bcd gradient during the past thirty years reported on the gradient that forms at the syncytial blastoderm stages after the nuclei reach the surface of the embryo, and ignored the earlier eight cycles of nuclear divisions that occur before the nuclei reach the surface.

Our recent work of (Ali-Murthy and Kornberg, 2016) shows that these assumptions are incorrect. In fact, the mature oocyte has Bcd protein tightly sequestered at its anterior tip in the same pattern as bcd mRNA, and after fertilization, the Bcd protein gradient forms first in the embryo interior and first organizes spatial domains of expression of target genes prior to syncytial blastoderm. These distributions of bcd mRNA and Bcd protein are not consistent with gradient generation by protein diffusion and suggest that the protein gradient is most likely generated by a process that involves regulated transport. These findings imply that the early Drosophila embryo is more organized and actively regulated than had been previously understood – that it is not entirely pre-programmed. This exciting conceptual advance should encourage more investigations of this fascinating stage of embryogenesis, especially now that new methods for analysis are available and now that there is a new appreciation of the way that the patterns form.